Women as Settlers and Claimants

Another unique feature of the Niagara District is that women participated in settlement of the region by petitioning for and receiving land grants as Loyalists or through their connection to male Loyalists. While some studies of women’s economic power in the colonial era have focused only on “those who had property,” the unique nature of land grants in Upper Canada meant that both widowed and married women participated in the settlement process even if they did not have control over their own property.107 The ability to submit land petitions and receive grants may not be considered economic power in the traditional sense but many families nonetheless benefited from women’s power to acquire capital in the form of land. During the early years of settlement in Upper Canada, “Women in their own right, especially unmarried women, were seldom given land.”108 Yet in J.K. Johnson’s assessment of petitions filed between 1815 and 1840, women account for 18% of all land petitions, many of which were based on their identity as Loyalists or their position in relation to male Loyalists.109

Most land petitions submitted by women focused primarily on the Loyalism of their husbands, fathers, brothers, or uncles. Jane McKerlie’s 1797 petition began, “Humbly Sheweth That your petitioner is Daughter of Peter McMicken,” and concluded, “prays your Honor would be pleased to allow her such a grant of Lands as is generally given to Daughters of Loyalists.”110 The council granted her “200 acres as the daughter of a Loyalist.” McKerlie’s petition added even more land to the family holdings, as her husband John’s earlier petition had resulted in a grant for 200 acres. The trend of husband and wife submitting separate land petitions was relatively common. After John McNabb received a grant for a lot in the town of Newark and 2,000 acres elsewhere, Isabella McNabb submitted an additional petition as “niece to Captain Angus McDonell of the late Regiment of Sir John Johnson’s Royal Yorkers, and wife of John McNabb Esquire.”111 The council ordered “in consideration of Petitioner’s connections and present situation four hundred acres.” The McNabbs also tried to acquire the land previously held by Angus McDonnell after he died but it is unclear whether the land was ever given to them. Although husbands assumed control of married women’s property under the principle of coverture, even if the property was granted to them based on their gender as daughters or nieces, women played a unique role in the settlement of Niagara through their acquisition of land.112

Promenade House (built by Elizabeth Thompson around 1819), Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario. Karen Whittle and Peter Hewitt, 2021.

Promenade House, Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario. Karen Whittle and Peter Hewitt, 2021.

Promenade House, Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario. Karen Whittle and Peter Hewitt, 2021.

Widowed women also took advantage of the offer of free land to Loyalists and their children. In 1797, Elizabeth Thompson provided a detailed account of her activities during the Revolution to support her petition for a grant of land. Thompson wrote that, “many times at the risk of her life assisted the scouting Parties of Loyalists and Indians with provisions,” and was even “imprisoned at the German Flats on suspicion of concealing spies.”113 She also mentioned that her father and brother had both served in the British army. Between 1790 and 1804, Thompson submitted numerous petitions to deal with land grant and management issues. She was given Lot 28 in the town of Newark, on which she built two houses, the first having been destroyed when the town was burned during the war. The second house still stands today, one of the few homes built by the original owner of the lot. While Thompson made no explicit reference to her husband, her daughter Anne’s petition for land mentioned that James Thompson had been a Loyalist, along with the rest of his family. Anne received a grant for 200 acres as a daughter of a Loyalist, though it is unclear whether Elizabeth received land outside of Newark.

Like Thompson, Catherine Clement of Newark included substantial information about her service to the Crown. In her 1795 land petition, she stated that she, her husband, and their five children were “zealous loyalists” during the Revolutionary War. While her husband and sons served in the military, Clement claimed that she too served the cause by “Supplying persons employed on secret Service with provisions & Intelligence and in forwarding letters to & from persons in the States for the information of Government.”114 The response recorded on the documents does not mention anything about Clement directly, but states that 2,000 acres had already been granted to the heirs of Lewis Clement and so the petition was considered answered.

Clement was dissatisfied with the council’s decision, perhaps because she was not given any portion of the previous land. She submitted two new land petitions in 1797. The first again focused on her activities during the war, such as having “forwarded several dispatches in His Majestys [sic] Service” and other supportive actions but the petition was denied based on the previous grant of land based on her husband and sons service.115 The council wrote, “the Board cannot grant specifically to her without deviating from the Rules they have laid down for their Conduct in the land granting Department.”116 Presumably, the council reviewed the grants made to the Clement family, noted that land had been granted to James Clement and his children, and so Elizabeth was not considered eligible for another grant, regardless of whether she actually held any of the land previously awarded. This demonstrates the underlying assumption held by the council that land grants made to men (husbands or sons) would necessarily provide for dependent women. Only in situations where there were no male relatives on which to depend were women considered eligible for their own grants.

Despite these principles, however, Clement’s third petition was successful, with only the brief comment, “Recommend for 300 acres family land.”117 This final petition, which seemingly succeeded in securing a land grant for Clement herself, made no mention of her service or loyalty during the war, but instead focused on her children upon whom she had relied since her husband died and who were now settled in the province. Since it seems unlikely that the rules had changed, the council may have finally relented to Clement’s insistence that her children were not providing for her and that she needed land of her own to survive. Clement’s two-year battle with the Executive Council to provide security for herself demonstrates her resiliency and determination to find support from the country for which she had served and sacrificed.

The persistence that Clement demonstrated in her pursuit of a land grant is also visible in the war loss claims submitted by women of Niagara after the War of 1812. The Board of Claims for Losses (BCL) appointed in 1823 to review war loss claims produced one of the most extensive collections of documents related to civilian life before and during the war. The archival collection includes over 27,000 pages of material such as handwritten claims, supporting statements, signed affidavits, reports, summaries, registers, indexes, minutes, and vouchers.118 A more complete exploration of the contents of these war loss claims can be found in Module 4, but a brief examination of the collection itself offers insight into the distinction between Niagara and other districts in Upper Canada in how women’s experiences were documented. Among the districts that were affected by the war, Niagara suffered more than any other, both in number of inhabitants experiencing losses and in total value of lost property. Following the war, the board reviewed 2055 claims submitted by inhabitants of Upper Canada seeking compensation for losses incurred during the war by either enemy or friendly forces. Inhabitants of Niagara submitted 678 (33%) of those claims for a total of £182,169 in losses, which is about 45.5% of the total losses for the province. The districts with the next highest number of claims were Western (20.2%), Gore (15.1%), and London (14.4%), with combined losses of £160,236 (40% of total losses).119 These figures indicate that the Niagara District suffered more widespread and substantial losses than any other district, which means it also produced more documentation of its inhabitants' experiences.

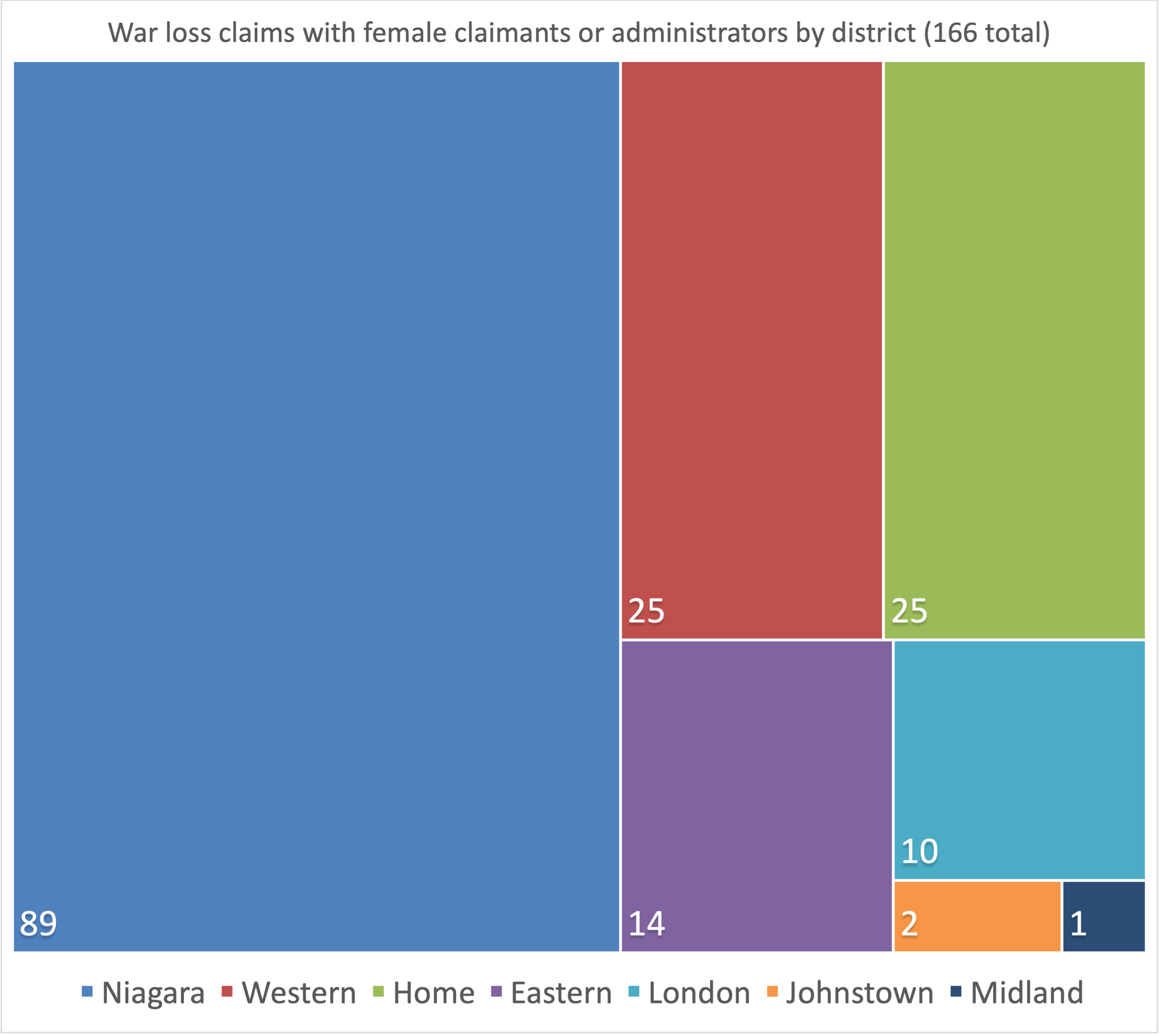

In particular, the experiences of women in Niagara are over-represented in the war loss claims. Women from thirty-eight different townships across seven districts of Upper Canada submitted or inherited 166 (8%) of all claims. 89 (53.6%) of those claims were submitted by inhabitants of Niagara, accounting for 13.1% of the claims from that district. In comparison, only twenty-five claims from the Western District have female claimants or administrators, representing only 6% of the claims in that district. The higher percentage of women’s claims in Niagara results from two combining factors: the intensity of the war in the district and the number of men from that region killed during the war. The value of losses in Niagara account for nearly half of all losses, suggesting that the extent of plundering and burning was more extreme in that district. Inhabitants of Niagara account for one third of all claims, indicating that the destruction touched more lives in that district. Finally, while women across the province suffered losses during the war and then took advantage of the war loss claim process to seek compensation, women in Niagara represent at least double the percentage of claims from that district compared to others. When combined with contemporary accounts from diaries, letters, and other legal documents, the claims submitted by women of Niagara provide invaluable insight into their experiences before, during, and after the war. Through these accounts, we can better understand how the war affected women in Upper Canada and how they worked amid destruction and displacement to preserve their families, communities, and the entire province.

This chart shows the distribution of women's claims in Upper Canada by district. Niagara District includes the largest group, with 89 women represented.

-

See, for example, Carole Shammas, “Early American Women and Control over Capital,” in Women in the Age of the American Revolution, ed. Ronald Hoffman and Peter J. Albert, Perspectives on the American Revolution (Charlottesville: Published for the United States Capitol Historical Society by the University Press of Virginia, 1989).↩︎

-

J. K. Johnson, “‘Claims of Equity and Justice’: Petitions and Petitioners in Upper Canada 1815-1840,” Social History/Histoire Sociale 28, no. 55 (1995): 225.↩︎

-

Established in the 1780s to facilitate settlement, the first Land Boards reviewed and approved petitions for land but were disbanded in 1794 due to claims of improper administration that benefited friends of the board. From that point forward, all petitions were reviewed by the Executive Council of Upper Canada. Library and Archives Canada, “Land Petitions of Upper Canada, 1763-1865,” March 22, 2013, https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/land/land-petitions-upper-canada-1763-1865/Pages/land-petitions-upper-canada.aspx.↩︎

-

RG1 L3, Volume 90, Series M, Bundle 2, 1795-1796, 328A, Petition Number 251.↩︎

-

RG1 L3, Volume 90, Series M, Bundle 2, 1795-1796, 328A, Petition Number 254.↩︎

-

For further discussion of coverture, see Module 4: Claims for Losses.↩︎

-

RG1 L3, Volume 90, Series T, Bundle Miscellaneous, 1791-1819, Petition Number 3.↩︎

-

RG1 L3, Volume 90, Series C, Bundle 2, 1796-1797, 90, Petition Number 155.↩︎

-

RG1 L3, Volume 90, Series C, Bundle 2, 1796-1797, 90, Petition Number 109.↩︎

-

RG1 L3, Volume 90, Series C, Bundle 2, 1796-1797, 90, Petition Number 109.↩︎

-

RG1 L3, Volume 90, Series C, Bundle 2, 1796-1797, 90, Petition Number 139.↩︎

-

For more information on Board of Commissioners and the archival collection, see Technical Module: Library of Canada Materials.↩︎

-

These figures may be somewhat inaccurate because Gore District was created in 1816 from townships previously in Niagara and Home Districts. Claims from townships like Saltfleet, Ancaster, and Barton could be categorized in either Niagara or Gore, whereas York township could be either Home or Gore. This discrepancy may account for differences in the tallies produced in other studies of the claims. Legare considers Ancaster, Barton, and Saltfleet as part of Niagara, whereas Sheppard includes Gore in his tally without commenting on the possibility of split categories. While Legare’s approach is preferable, her tallies do not include figures for the entire province to provide for comparison. Because this study focuses on claims submitted by women in Niagara, the distribution of claims throughout the province used here is synthesized from Sheppard’s work, but the specific analysis is based on a subset of the original claims. See Legare, “From the Ashes,” and Sheppard, Plunder, Profit, and Paroles.↩︎